Career Development Challenge of Contemporary Female Factory Workers

- Amelia Kyaw

- Apr 9, 2024

- 8 min read

Authored by: Jing Chen, Wanting Sheng, Qinglan Zhang, Xinyan Zeng, Yizhi Peng, Chunyu Gu, Lingling Zhao, Huanyu Zhou

Research Background

As Chinese female factory workers contributed to the modernization and industrialization of China’s society, their career development and corresponding problems caused by various factors are underreported. Due to China's reform and opening policy, the reformed household registration system and industrialization have boosted more rural labor force, particularly, women, to migrate to metropolitan cities (Zhu, Chunyan, et al.,2013). As a result, a majority of Chinese female workers earned the chances of working and achieved financial independence (Pun, 2005).

However, various limitations hinder the further career development of female factory workers. Previous studies have analyzed this phenomenon at the macro level regarding social policies, social norms, and employment preferences. Some studies have shown that women workers received career discrimination since they lacked urban household registration (Honig, 2009; Pun, 2005). Other works showed that Chinese female factory workers were affected by the patriarchal culture in society, believing that they belonged to the state of attachment or dependence in the family, and thus chose to quit their jobs frequently when they were needed for household duties (Jaesok, 2015). At the same time, a majority of factories tends to presuppose unbalanced opportunities for gender occupational mobility, income, and status change, resulting in gender inequality (Pun, 2005).

Based on the existing problem, this study aims to reveal and analyze the plight of Chinese female factory workers’ career development at the micro level. Focusing on education and skills background, family expectations, and gender stereotypes, this research will explore and present the authentic problems and corresponding thoughts based on first-hand data, to help them garner more attention from society and to dispel social misunderstandings.

Research Method

To narrow down the description and to approach the accuracy of data collection, participants were all female factory workers randomly selected from the same factory with different work positions in the same city of China.

This research used combined methodologies to approach the desired results, which intertwined quantitative survey design and quanlitative interview. The survey design refers to an online anonymous questionnaire containing close-ended and open-ended questions. The qualitative interviews were conducted with a subset of the participants selected through purposive sampling. which were conducted in person at the factory.

Design

The online survey was distributed to 54 participants and received 50 valid samples. The close-ended questions collected their demographic information and the three major aspects -- education level and salary, family responsibility and the conflicts between work and family, their cognition of gender equality, and previous responses toward gender inequality. This questionnaire mainly collected data and combined qualitative and quantitative methodologies to preliminarily analyze the situation faced by female workers. Data collected from the online questionnaire was analyzed using descriptive statistics such as mean scores and frequency distributions. The statistical analysis was conducted by using the Excel software.

After synthesizing the data from this online questionnaire, we conducted semi-structure interviews which classified questions with 15 workers of different ages, years of employment, and job fields. In-person interview, which was recorded with their permission, was aimed to hear female workers’ authentic voices targeted various themes. interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed with participants’ permission. The data was analyzed with a thematic analysis approach.

Findings

Finding 1: Female workers with a lower education level engage with simpler manual work, which earns less money than the local average wage.

According to the data, it is reasonable to infer that most of female factory workers are generally under-educated. Results of the survey reveal that 58% of female factory workers have junior high school education or below, and only 1 out of 50 in the survey have a university degree. Correspondingly, data shows female factory workers whose education level stays below senior high school all work in assembly lines, performing basic manual operations such as wrapping packages.

Figure 1 - Educational background of female workers

Moreover, results reveal that female workers with lower education made less money. The survey shows that 96% of female factory worker earn less than 5, 000 RMB a month, which is below the average salary (8, 000 rmb) of the city where their factory is located. Only 2 interviewees earn 8, 000 rmb and above a month; however, they all own a community college educational background and have a position of sales.

Furthermore, the data indicates that female factory workers with lower education have a limited wage range. This is because their assembly line work highly relies on the products they manufactured. As one female explained: “our salary is counted by the pieces of products we made. More products we made, more money we could get.” When the cost of a single product is reduced, their wages are decreased correspondingly. As one interviewer said: “I don’t know why the price of single product the factory gives to us is lower than before. But this situation frequently happens, and the money I make is unstable.” In this circumstance, more female workers choose to spend more time working to make more money, as the result shows that 92% of female workers work for 12 hours per day. However, their wages will not exceed too much due to their limited lower wage base.

Finding 2: Female factory workers recognize that they do receive family expectations which require them to take family responsibilities and strive in work simultaneously. Particularly, child care is the major issue of the imbalance between family and work.

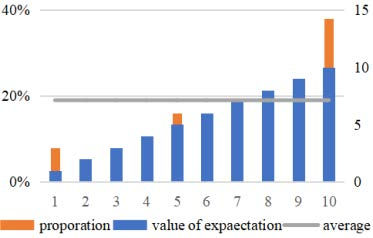

Results show that female factory workers perceive they receive higher family expectations concerning taking more family responsibilities, earning higher salaries, and occupying higher job positions. On the one hand, the different values shown in figure 2 reveal what female factory workers perceive to be expected by their family members concerning their commitment on family responsibilities. The setting uses numbers from 1 to 10 to represent different levels of expectations. Based on the average result of expectation, 6.66 (figure 2), it shows that workers believe that their families expect them to put more time and effort into the housework. On the another hand, female factory workers perceive that their family members have higher expectations and requirements for their work situation based on the average result 7.12 (figure 3).

Figure 2 - Family responsibility expectation perceived by female workers

Figure 3 - Work expectation perceived by female workers

Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that female factory workers believe their family members expect them to take care of the family and perform well in their jobs simultaneously. In this case, two aspects of expectations potentially cause pressure to female factory workers. However, the result of the survey question -- “Do you agree your family’s expectations cause your pressure?(figure 4), shows a weak connection with this hypothesis. 72% of female workers disagree that these kinds of “expectations” produce overwhelming pressures and troubles that severely affect their daily lives. Less than one-third (28%, 14) of subjects confess that they feel pressure.

However, in-person interviews show inconsistency in the less pressure which female workers recognized in the survey. 15 subjects who accepted the interview expressed that they feel great pressure when they think about the expectation from family members catering on necessary family responsibilities and career progress.

Particularly, the interview results show how they deal with the imbalance of family and work. Child care is the major issue they are facing when conflicts happened between family and work. 10 females choose to leave their children in the care of older family members and cooperate with their spouses to do housework. One worker, who is 35 years old and has a 3-year-old son, told that: “my children are raised by my mother-in-law in my hometown, and my husband works with me here, usually sending money back”.

Nevertheless, the separation between children and parent is a compromised method that could merely solve the problem temporarily. Interviewees confessed that they missed their kids so much at the beginning days of factory work, and they were frequently distracted from work. A 30-year-old female worker who comes from a small town told: “When I left my daughter and worked in there in the first two months, I can’t help to missing her and was often disctracted. My daughter misses me, too. And my mother told me that she still cries when she cannot find me, even though I have worked outside for 2 years. It is not a long-term solution. I make my mind to go back to her after I finish this season’s work and receive salaries.”

More importantly, interviewees who have the issue of child care all insisted that they would only work in the factory for no more than one or two years, and quit their jobs and come back to hometown, if their children fail to be raised and educated in the same city with them.

Finding 3: Inconsistency exists between female factory worker’s cognitions and behaviors toward gender inequality.

The results show that female factory workers presented inconsistency when they confront gender inequality in the aspects of cognition and action. On the cognitive level, the data of interviews illustrate that female workers rejected the Chinese traditional principle which claims that men should work outside the home and women should stay at home. They firmly believe that men and women are separate individuals, so no one perceives that women have an obligation to care for their families while men are at work. “If my husband and brothers have the right of working in the big city, why can’t I ?” -- such a quote from an interview, who has been married for over 5 years and has a 3-year-old son, is not a rare claim among the subjects when they were asked whether they believe and agree that women should stay at home and support men work outside. Except for family circumstances, interviews expressed that they believe they have similar rights and competitiveness with male workers, as a quote from a 24-year-old female worker -- “I believe I can earn similar money compared with males since I could handle the work they can do even the work they can’t.” Similar expressions were often heard, which reveal that female factory workers do chase for gender equality and reject gender inequality in their minds. However, female factory workers did not present objections on the action level when they experienced or witnessed gender inequality happened in the factory. According to the questionnaire, inequalities of “access to promotion” and “payment” are reported as gender inequality that happened in the factory. Among these problems, only about 5% of the women chose to report to their superiors, but 70% of the women chose to quit their jobs without reporting. These negative responses resulted in less valid solutions to address gender discrimination.

Conclusion

Overall, this study helps us to understand the difficulties female workers face in reality. Firstly, 88% of female factory workers analyzed have lower level of education, and their monthly average salary is less than 3,000 rmb at the local level. Their salaries are deducted when the single price of products falls, which means that their payment amounts relate to the trend of overall economic situations.

Secondly, female factory workers perceive that they do receive higher expectations from their family members in both family and work aspects, which cause great pressure on them. Child care reported as the major issue, which will drive female workers to give up their jobs for the sake of companying kids. Consequently, the mental burdensome tends to cause great obstacles to female workers’ career development.

Third, female factory workers illustrate inconsistency in their cognition of pursuing gender equality and their action of resisting gender inequality. They disagree with the traditional Chinese viewpoint which claims that “men outside the home, women inside” but fail to confront gender inequality with positive actions. In this way, social supports from government and companies should help female factory workers to have more guaranteed and long-term career development.

Comments from the Evaluation Panel

Overall, your report is well-written. The topic selection, background, and research design sections demonstrate clarity, concision, and focus from the outset. Within the Research Findings, the revised analysis evinces more rigor and coherent logic after modifications, with the cited interviews providing sturdy support for the arguments. Particularly commendable is noting inconsistencies between questionnaire and interview data when presenting the second and third findings. However, it is regrettable that there lacks further discussion and analysis into the reasons behind such inconsistencies, which could have provided fruitful insights. Regarding formatting, you have largely adhered to report requirements, though some charts still lack standardization and professionalism. This encompasses inconsistent numbering and correspondence between charts, absent titles, and inappropriate chart types. For instance, Finding 1 should use a bar chart reflecting average income across education levels of female workers, whereas the current chart fails to convey the income-education relationship. The two charts in Finding 2 should adopt pie charts to demonstrate score proportions or bar charts for score frequencies, with the scores themselves only necessitating depiction on the categorical axis. We hope you can sustain your strengths while continually refining deficiencies, achieving greater rigor and professionalism in future research.

Comments